Generally speaking, I don’t really like making New Year's “resolutions”, but try to hit themes I want to tackle. This year, I’d like to have a better handle on my acid reflux - triggered by stress, eating certain kinds of food, eating at weird times, etc.

As I began to stress eat at 4pm on January 6th watching the pillars of US Democracy crack, I realized this was the fastest I had ever given up a New Years resolution.

This isn’t like normal years where people just casually make New Year's resolutions about diets. We have a pandemic going on where obesity is a clear risk factor and we simultaneously have a spike in food insecurity due to layoffs. This is the bizarro version of the double burden of disease.

Food is inextricably linked with our health, so I’ve been thinking a bit more about it. This could be a whole book that I’m unqualified to write, so I wanted to hone in on a few things.

Some Context Around Food and Healthcare

Let’s just set the stage here. There are entire papers and dissertations about how food issues become healthcare issues so I’ll just give high level points (NPR has a great summary of these here).

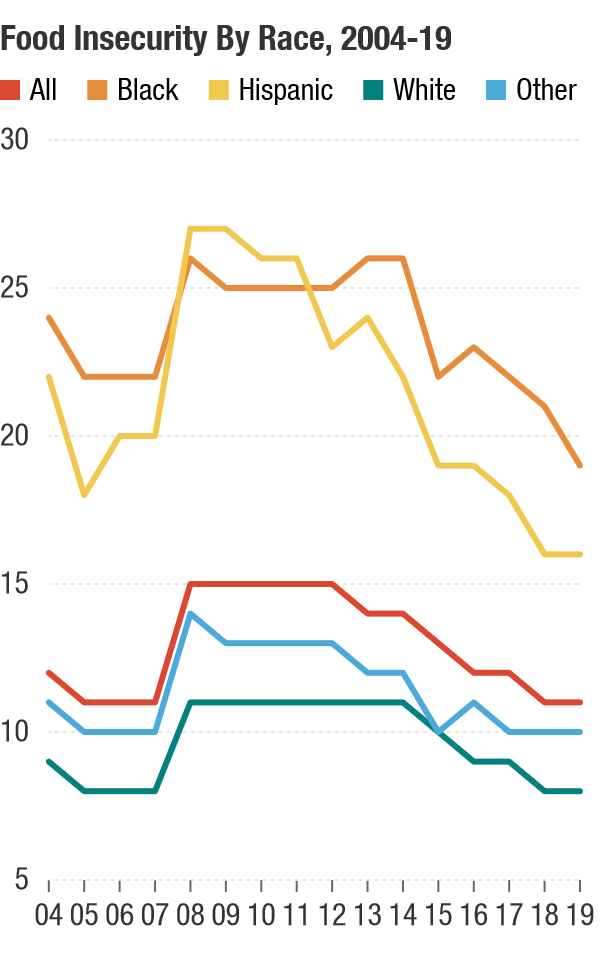

Pre-pandemic, 10.5% of US households saw some form of food insecurity, jumping to 23% during the pandemic (potentially closer to 30% for households with children). This disproportionately impacts black and hispanic communities.

About 19 million people live in a food desert -- though accessibility to grocery stores has actually gotten better over time.

There’s an obesity epidemic, with prevalence jumping from 30.5% in 1999-2000 to 42.4% in 2017-2018 in adults. Relatedly, the prevalence of obesity-related conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, etc. is also increasing rapidly.

While general food costs have increased about 2% per year (approximately in line with inflation), fresh vegetables have grown closer to 4% per year. This is even higher in some food deserts.

There are so many more to cite. But beyond that, we have demonstrable data across many studies that food interventions work well and have a better return on investment vs. most other interventions.

Geisinger (which is both a payer and provider) launched a Fresh Food Farmacy to prescribe food to diabetic patients from a pantry it ran along with diabetes management classes, pharmacist access to manage medications, etc. The outcomes for the pilot saves nearly $200K pet patient per year relative to $2,400 spent. Geisinger is now growing this out to other areas.

Tailoring the meals actually makes a difference, too. A non-randomized study looked at patients that received medically tailored meals, normal non-tailored meals (via Meals on Wheels), and a matched control group that didn’t receive these interventions. Turns out that just giving patients food already reduces costs form inpatient admissions and emergency transportation, but when you tailor the meal for the actual patient’s condition they save even more. Yes it’s non-randomized, but this is also just common sense. For all the talk about personalized medicine through software, algorithms, genetics, etc., we can actually improve outcomes literally by giving patients the right food.

These studies are the easy to experiment and measurable food interventions; if you invest even further upstream in better food for populations at-risk BEFORE they become sick, you’d see savings at a population level as well.

There’s a lot more evidence I could bring up, but I want to dive into a few areas I’ve been thinking about.

Food Logistics + Prep

There are three core logistics problems that have to be solved to make food better integrated into patient care.

1) How do we make it easier for the doctor to “order” food for patients?

We need to make it easier for doctors to actually prescribe food, track that they prescribed it, reach out to patients if there’s an issue, and measure outcomes.

To prescribe food, there needs to be a connection between the EHR and the end destination where patients get food. The easiest way to do that is for the provider to actually own and run the pantry/grocery store because then the integrations you need are minimal (which seems to be what Geisinger did its Food Farmacy). But if you want to be able to link to third-party grocery stores that are more convenient for the patient, you need to figure out a way to have orders from the physician go to the grocery stores, have payment flow to the grocery stores for the approved items, etc. This is non-trivial, but if we don’t have a “one-click order” level of simplicity for the provider or care team, this will never see adoption. I think connecting EMRs to grocery or food delivery applications with eligibility on foods that are good for X disease might be one way to connect these systems together.

And how do you make it easy for doctors to document that they’re ordering food for the patient and get reimbursed? Anecdotally this seems to just be done through free-text or ad-hoc partnerships but no widely adopted process. One area I’m interested in is the introduction of Z-codes as a billable ICD-10 code. These haven’t quite spread (to my knowledge) but having codes like Z59.4 (Lack of adequate food and safe drinking water)makes it much more likely that providers will actually track this, especially if they’re getting reimbursed for these actions. With a structured billing code we can also track how these food prescriptions get used across providers. That being said, the fact that most food pilots have happened with providers in some sort of value-based care arrangement (Geisinger, Medicare Advantage primary care providers, Kaiser Permanente, etc.) means that having billing codes used by fee-for-service providers might be irrelevant.

2) How do we make fresh produce more accessible and easy to prepare for patients?

When I graduated college, I was determined to learn to cook, so I signed up for Blue Apron because it seemed easiest (pre-portioned ingredients delivered! 3 steps! 15-20 minutes to make). The first box I ever got contained a butternut squash, which is cylindrical, and told me to cube it. That was the instruction, cube this squash. Bruh what.

After spending like 10 minutes looking at Martha Stewart videos on cooking basics I began hacking away with my dull knife. The meal took about 50 minutes to make in total, and I wondered if it even made sense to learn to cook when I slide into old habits and pick up food for roughly the same price down the street. Actually, for a period of time I drank 2-3 soylents a day, but that’s a whole other story.

Many of the patients that would most benefit from food interventions have the least time or money to invest in cooking, which is one factor why easy, less nutritious meals become default. Grocery stores in food deserts end up closing because they can’t compete with convenience stores like Dollar General that carry more unhealthy shelf-stable food.

Companies like Amazon are testing things like “online-only grocery stores” that are delivery-only using cheaper and more centralized real estate. They also integrate SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits to grocery checkout as a pilot with the USDA along with offering a cheaper Prime Membership. This can make the margin profile of fresh produce better and more convenient for patients if it’s delivered right to them.

It will also likely require some form of local/state government to better incentivize new grocery stores or stores to hold fresh produce. There’s a good NPR podcast about a town in Tulsa that did just that. During the pandemic, several local governments worked closely with produce distributors like The Common Market and Aramark to get weekly boxes of produce delivered to food insecure households. Figuring out a more permanent scaled version of this would be great.

I think we’ll see a step function improvement in patient nutrition when healthy, fully prepared meals can be delivered cheaply with minimal work needed from the end user (bonus points if the food fits into a familiar taste profile the patient is used to).

There seems to already be interest here from health systems. Mt. Sinai invested in Epicured, providing low FODMAP (a type of carb that triggers gastrointestinal issues) and gluten-free meals to patients. Kaiser Permanente invested in Everytable. These companies provided prepared food to people, which is really as easy as it gets.

The cost of preparing and delivering fresh meals is going to get cheaper and cheaper over time. Robotic food preparation drops cost significantly (Chowbotics has automated salad bots in hospitals). Last mile delivery is getting cheaper as it’s bundled into other goods thanks to Uber, or with fully automated caravans doing grocery delivery. Ghost kitchens are lowering the cost of the space needed to prepare food by creating shared kitchens.

All in all, there’s going to come a point where it economically makes more sense to be in a subscription to a prepared food company, and people will opt-in to it because it’s convenient. I think at that point it’s a really appealing sell to patients - not only will we deliver the food to you, you literally just need to heat it in the microwave. That’s probably the only way to compete with shelf-stable food - make it equally as convenient.

3) How do we make payment easier for patients?

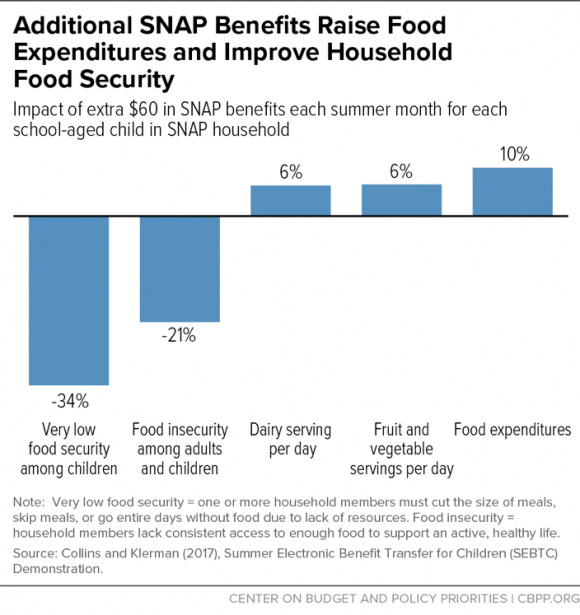

A “rain is wet” observation: patients need money to pay for food if they’re expected to change their diet. There’s lots of data that shows that SNAP benefits have been one of the largest drivers of reducing food insecurity and can help increase the number of servings of healthier foods.

The inverse is true as well -- low income patients with diet-related disease see increases in admissions towards the end of the month when food benefits run out and patients are forced to stretch meals.

We need easier ways to give cash to patients at-risk because they can’t pay for food. I can’t claim I have any great ideas here, but I would think we have better means to drill down into individual customers to the point that cash can be given based on their individual need vs. based on where they are in a given month.

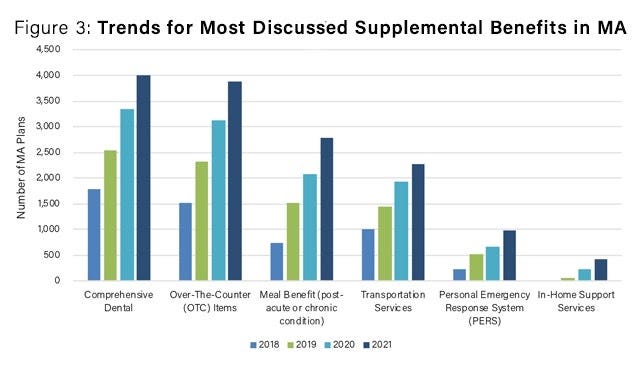

One interesting area to watch is Medicare Advantage, which can now cover meal benefits in their supplemental benefits and is on the hook financially for a patient’s whole health. The meal benefits supplement seems to be growing quickly (though frankly I thought it would be much faster). With MA plans having a heavy incentive to get an understanding of how food fits into each individual patient's care regimen, we might learn some lessons on how similar systems can be deployed at scale.

Food Tracking

I’ve been trying to use some acid reflux trackers, and to be honest, they all suck. Sure, some of them suck because they’ve never met a UI/UX designer in their entire life. But honestly the process just sucks: Each time you eat you have to remember to log it, the time, the portions, spiciness, etc. It’s a huge pain in the ass and I always do it like a day or week later, all at once.

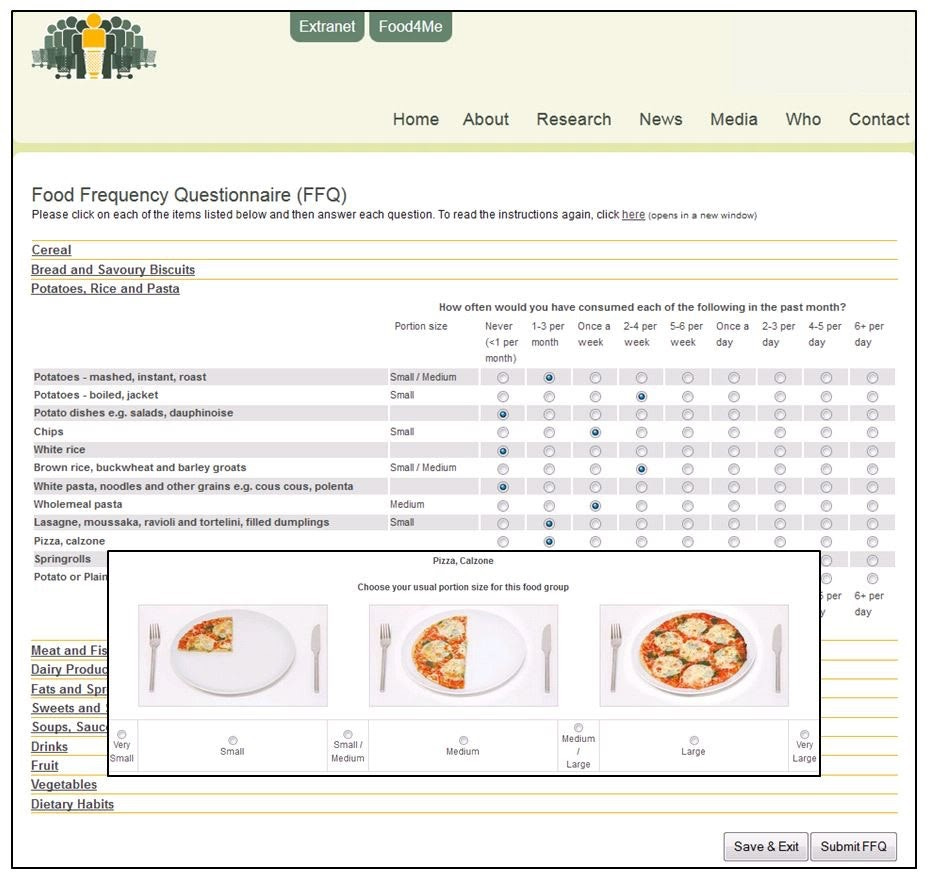

Actually this is a huge problem when it comes to things like nutrition studies which are almost always observational studies that require patients to fill out Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ) that are designed for you to obviously lie so the study lead doesn’t think you’re a glutton. Plus they’re generally limited to standardized groups, how am I supposed to add “omelette with the leftovers of the last 3 meals”?

Plus, you have to remember what you ate. The most egregious version of this I’ve seen is from a 1994 study:

Data on the intake of food and supplements were collected during in-person interviews by trained interviewers between May 15, 1988 and December 15, 1990 in subjects' homes (or at the Beaver Dam Eye Study site when requested by the participant). This occurred approximately one month following the eye examination. Participants were asked about their usual diets over a one-year period of time, 10 years before interview. A series of questions about lifestyle during that time preceded dietary questions to help the participant orient to that past time period.

Lol imagine someone asking you to remember what your diet was like 10 years ago, and to “get you in the mood” they asked what kinds of hobbies you had during that time. I don’t even remember what I ate for breakfast literally today.

The problem with including nutrition in studies, healthcare, etc. is that self-reporting is not a reliant measure + the physiological response to food is highly variable per person, so generalized findings might not be right for an individual.

Some things I think might change this:

Passive tracking of food orders - I remember a few years ago seeing that you could connect your Sweetgreen app to Apple Health for calorie tracking. If you imagine a world where ordering meals at home becomes more frequent over time thanks to food product/delivery costs going down, then having something like a unified health record being able to track all of those orders in one place would make meal tracking passive. It would also put the onus on businesses instead to track things like portions, calories, etc. instead of each customer having to figure it out. Many states like New York are already mandating this, though it seems like it hasn’t had the impact people hoped..

Machine vision to identify food - As machine vision becomes better at identifying objects, it can make it easier to log and identify our food. Google’s Cloud Vision API gives us an example of that. If we ever move to a world of augmented reality glasses this will be way easier since this can be captured passively, but for now even a prompt to take a picture of your food (which your phone can tell based on gestures from your arm if you’re wearing a watch) is still better.

Longitudinal tracking of physiological response - Companies like Levels have healthy people tracking their blood sugar. Virta focuses on using ketogenic diets to reverse type 2 diabetes and measures patient outcomes plus HbA1c over time. A new study looked at the types of “good” and “bad” gut bacteria that exist as a response to different diets, which were different even among identical twins with different diets (suggesting diet and not genetics change gut bacteria).

As more people start tracking biomarkers when they’re healthy, we’ll have a better system tracking your body's individual response to food. With more granular data per person, we can then start cohorting people who have similar responses to food and understand the specific foods that are good or bad for them (e.g. way more personalized nutrition guidance). Some part of me hopes that maybe tracking the physiological response to food can also help us “fingerprint” different foods (e.g. if your blood sugar spikes a certain way every time, then you just need to say it’s “Twinkies” once and it’ll passively capture that in the future). But I’m guessing there’s just too much variance to how even our own bodies respond to food to actually do that.

Food as a touchpoint

You know what I do three times a day? Eat food.

You know what I don’t do three times a day? Think about my primary care provider. Except for days where I’m hungover and think I might literally die.

Food is social, food is the cornerstone of lifestyle changes. If you go to any online patient community for a given chronic disease you’ll see a disproportionate amount of tips related to food, recipes, etc.

Food can give healthcare companies reasons to have consistent and frankly more ordinary touch points with patients. Not every encounter with a patient needs to be so serious and heavy.

A few ways I’ve been thinking about this.

Food as a home touchpoint - Food delivery and cooking can be a good way to understand and improve other issues in the patient’s home. Whether it’s guiding patients through a cooking session virtually or delivering groceries/meals, these interactions can be used to expand the conversation with patients to other healthcare needs that the conversation can build up to or have vitals checked if you’re already delivering food. I look at companies like Dumpling, which is trying to differentiate itself in the grocery delivery space by letting the shoppers build their own customer relationships and service offerings. I think it would probably make sense for shoppers with end customer relationships with elderly or low-income groups to potentially help check-in with the customers healthcare tasks while they’re there.

Food as trust building - I think of this primarily for people that have low-trust in the healthcare system. For groups that feel the healthcare system has failed them, many turn to more natural therapies and that usually is the form of food or supplements. By having more integrative medicine avenues where food is a centerpiece of the treatment, we might be able to keep those patients closer to the medical world. Otherwise they can end up in much more dangerous and unregulated channels online. Obviously there’s a bit of a cautious dance to be done here so that a patient isn’t replacing necessary interventions with only natural ones.

But I think generally, food is a naturally trust building exercise -- you don’t cook or eat meals with people you don’t trust. Maybe health teams will have a better time talking and convincing patients to do difficult things if they establish trust with them during the more routine daily parts of life.Cooking as Therapy - Building on the idea of food = trust, a psychiatrist friend of mine told me that his ideal practice would be one where he could do activities the patients wanted to do while having a session (including cooking a meal together). There’s logistical reasons why this would be tough, but I liked the idea of some kind of “therapy over a meal” concept. Right now I basically watch cooking videos on YouTube as a form of relaxation anyway so…

Dietitians and Flavor Profiles

As I researched this post, a common trope seemed to be “doctors don’t get enough training in med school on nutrition” (e.g. this study) and that nutrition isn’t heavily incorporated enough into treatment regimens.

IMO we need to stop expecting our physicians can learn and implement everything in medicine, and instead specialize roles where possible. This is exactly where dietitians can play an important role -- especially because the engagement with the patient looks extremely different vs. a regular visit with your doctor. You’d want your dietitian to have more regular touch points outside of the clinic and very easily accessible for quick questions.

There are 106,622 registered dietitians (with a specific degree, which is not the same as a nutritionist). That’s about 1:3078 people in the US and they’re not geographically spread where obesity is more prevalent as a % of population. We need more tools that will scale dietitians, which several startups like Season and Wellory are building. Insurance actually will cover dietitians in a lot of cases if it’s part of a program your provider prescribes. But this is usually for patients that already have an obesity related disease. Now that we can assess when patients are at-risk for developing these diseases in the first place, we should figure out reimbursement that incentivizes payers to prevent patients from moving from being at-risk to having a food related etc. diagnosis (obesity, GI, cardiovascular, etc.).

Another problem with dietitians is that many don’t try to work within cultural nuances. Suddenly throwing someone into a totally new flavor profile or type of food requires really drastic changes not only to the patient’s diet, but the entire family that’s eating as well. There’s a good New York Times article about this, but what was pretty stark when looking at the data is how dietitians skew predominantly white. Food is one of the cornerstones of most cultures, so making it easier to transition into healthy habits by swapping out ingredients within existing recipes a patient already makes or slowly introducing new meals with similar flavor profiles might increase adherence and make the transition easier. Yes, if you replace paneer with tofu you’ll get a lot of angry South Asian families yelling at you, but that’s still an easier transition than throwing wilted kale in the mix.

Food For Thought lmao

A few final random things.

“But Nikhil, didn’t you write a whole post about why we shouldn’t rely on hospitals and insurers to be so involved in social determinants of health like food?” Shhhh, I contain multitudes. It's cool. I get stuck here because it’s clear that food should be more integrated into the healthcare system, but I don’t think they’re the best entity to actually execute this. Maybe it’s public health departments? Maybe it’s hospitals? Maybe it’s primary care teams that take on a patient’s total spend and work closely with community-based organizations like Meals on Wheels, God’s Love We Deliver, etc.? I see pros and cons to each version.

In an ideal world we set up an actually competitive system where existing healthcare companies start including this naturally in a cost-effective way. I’m watching to see how food integration plays out in an area of healthcare that’s (kind of) competitive like Medicare Advantage, which I mentioned earlier can now cover some meal benefits.

The integration of food in healthcare is most critical when it comes to kids, because that’s when habits and taste are getting formed. Part of me wonders if we should have equally aggressive campaigns for sugars/fats the same way there were aggressive campaigns when I was in school around tobacco. Childhood obesity is a clear issue in the US (18.5% of kids 2-19 are considered obese). A big part of this is nutrition that kids get in school. Michelle Obama implemented programs designed to have healthier lunches.

But if kids are food insecure or eating low-nutrition meals for the other two then it sort of defeats the purpose. On top of this, there’s a very delicate dance of encouraging younger children to be mindful of their weight while also not creating body image issues. Weight Watchers acquired Kurbo Health in this space, and faced quite a bit of backlash.

An omission from this post is the fact that the government subsidizes growing corn which makes it much more economical to grow it and produce corn syrup. There is a whole conversation to be had around the agricultural policies that are even further upstream from food itself but that’s getting a bit too galaxy brain for this post.

If we want to have better health outcomes, we need to focus upstream on what we’re eating.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “f*** butternut squash”

Twitter: @nikillinit

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Would love the galaxy brain version of this with a deep dive on how the corruption and greed of big farm-a and impacts health of communities for generations and is intricately intertwined with the corruption and greed of big Pharma/HC

Great article, thanks for the comprehensive overview. I'd love to connect @freshmednyc @performancekitchen