I’d like to talk about the term “non-profit”, because it seems to take on a very different term in the healthcare world.

See hospital non-profits get a lot of the nice tax benefits afforded to non-profits: breaks on income and property taxes, donors can write off donations, access to cheaper bonds/debt, etc.

And yet there’s something odd about hospital non-profits.

For example, here is a list of the ten most profitable hospitals in 2013.

And here’s a quote from the CFO of the non-profit health system Christiana Care.

We know that we want to maintain a margin that will provide us with the resources to continue to invest in our infrastructure to deliver optimal services. And we need to continue to invest and develop the people who will lead us in our strategic aims as well as continue to invest in innovative tools and strategic partnerships. It requires a certain margin to do those things.

Wait a minute hold on…

Questionable tax status, reinvesting profits in infrastructure, people angry at how much the CEOs are making…

I actually think there are more profitable non-profit hospitals than unprofitable for-profit tech companies.

It’s important to understand nonprofit hospitals because they make up ~57% of hospitals in the US. The status of “nonprofit” was established for hospitals during a time where most care done was funded by charitable donations about 100 years ago.

While the rules have been revisited every so often, since we’re going to have to rebuild a lot of the healthcare system post-pandemic anyway it’s worth rethinking whether this designation still makes sense. Here are some of the reasons I think nonprofit hospitals are problematic.

Charity Care + Uncharitable Things

The main justification hospitals make for the “non-profit” status is the amount of “charitable care” or community benefit they provide. Until the Affordable Care Act, hospitals could effectively make up what that meant. After the ACA, there were some additional conditions they had to report, but those are virtually unenforced.

One of the main things these new rules were trying to address was the ruthless collections process that hospitals used to hound low-income and uninsured patients for their bills. So thank god that’s been dealt with, right?

In June, ProPublica published a story with MLK50 on the Memphis, Tennessee-based nonprofit hospital system Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare. It brought more than 8,300 lawsuits against patients, including dozens against its own employees, for unpaid medical bills over five years. In thousands of cases, the hospital attempted to garnish defendants’ paychecks to collect the debt. -Propublica, 9/29/2019

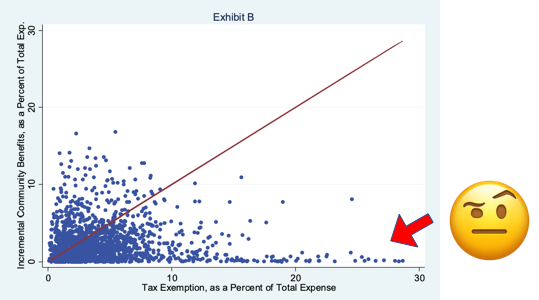

In fact, when you actually look at whether non-profit hospitals provide enough community benefit vs. their for-profit counterparts to warrant the amount they get in tax exemptions, the answer is “yes for 62% of nonprofit hospitals, but it highly depends on the hospital with some egregious outliers”. This paper is a great long read that goes into the nuances.

In the figure below, the dots above the red line are nonprofit hospitals that do enough community benefit to warrant the tax benefit, the ones under do not.

A separate study looked at charitable care across a basket of 2563 nonprofit hospitals, and found that hospitals with larger net incomes contributed to less charity care.

The amounts of charity care relative to overall net income were smaller for [nonprofit] hospitals with larger overall net income. The top quartile of hospitals provided $11.5 (uninsured) and $5.1 (insured) charity care for every $100 of their overall net income; the third quartile of hospitals provided $72.3 (uninsured) and $40.9 (insured) for every $100 of their overall net income.

Pricing, Quality, and Risk

Okay so community benefit is up in the air, but at least they’re cheaper right?

By analyzing newly-released data from Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealth on insurance claims from 2007-2011 that covered 28 percent of individuals with private employer-sponsored health insurance in the U.S., the authors were able to find enormous variations both between different geographic regions and within those regions.

“One of the things we found is that not-for-profit hospitals don’t price any less aggressively than for-profits. We subsidize not-for-profits to the tune of $30 billion annually, in the form of tax exemptions, and we have to ask what that money is getting us,” says Cooper, co-author of the study.

Okay but obviously the outcomes are better for patients right?

The only good study I could find examined hospitals that converted from non-profits to for-profits. They compared the converted group against other non-profit hospitals that had remained non-profits (control group). If you compare the numbers preconversion and postconversion against the controls, they had just as solid outcomes after converting.

They charge as much, potentially have similar outcomes, but then must be in riskier value-based contracts right?

Just 1.9% of net patient revenue for not-for-profit (NFP) hospitals in 2018 came from risk-based payment, according to a credit-rating agency. -HFMA/Moody’s

Lack of Regulatory Oversight

In many cases, the enforcement of the requirements to maintain “non-profit” status is virtually non-existent for hospitals partially because they largely get to define a lot of the metrics they’re governed by and submit the data.

Just to illustrate how messy that is, the paper from earlier mentions in its limitations section that it could only link the necessary data for 2/3rd of non-profit hospitals to determine community benefit, and in many cases the numbers between those sources didn’t even add up.

State governments have a bit of a tricky time navigating this scenario too, since nonprofit hospitals tend to be the largest employers in many states and legislators tend to try and get them more federal dollars to bolster the local economy. However, many states are starting to realize how big of an issue it is when they’re too large and tax-exempt, and we’ve seen lots of states suing nonprofit hospital systems ranging from Chicago, to Pennsylvania, to New Jersey.

a judge in New Jersey went so far as to say that if all nonprofit hospitals were operated like the one in Morristown, “then for purposes of the property tax exemption, modern nonprofit hospitals are essentially legal fictions.”

And just like Suits, this is probably another legal fiction that needs to unceremoniously end.

An interesting thing I learned is that non-profits technically don’t fall under the jurisdiction of the FTC for antitrust issues and rather have to be examined by the Department of Justice. This makes examining these issues a complex legal undertaking, particularly bad as non-profit consolidation has increased rapidly. This is old data but it’s likely even worse in the last 8 years.

“Reinvesting”

Non-profits can’t return money to shareholders, so hospitals have to invest into things that “further the mission of the hospital”. This has turned them effectively into diversified business holdings with sizable investment portfolios that include corporate venture capital arms.

More interestingly is the amount that seems to go into reinvesting in the facilities. This can include everything from investing in shiny new objects with questionable improvement in outcomes like robotic surgery. But it also can include investing in real-estate. Have you ever noticed how pristine non-profit hospitals look?

Non-profit hospitals get access to tax-exempt forms of capital to help fund a lot of these projects, and get to avoid property taxes thanks to the designation. In fact, if you look at where the big chunks of their tax-exempt savings come from, it’s bonds and property tax.

If an organization has to reinvest its profits into the places that will get the most tax benefits, of course it’s going to choose the extremely capital intensive projects like construction and equipment. But then it’s no surprise they have to consistently increase prices to maintain that kind of overhead. Maybe we shouldn’t be incentivizing that type of reinvestment?

Now, To Un-Non-Profit

The reason this is important today IMO is because in the aftermath of COVID care, many “non-profit” hospitals are going to be the ones that absorb the bailout money that’s coming down the line. COVID is going to be used as a justification for their “non-profit” status, but the reality is that it was problematic even before this.

What’s the solution? I’m not a policy wonk, but a couple things that could potentially help:

Setting up better emergency Medicaid systems that can quickly cover uninsured patients in emergency situations and increase Medicaid coverage and reimbursement instead.

Remove the non-profit status and redirect the tax-exempt money to safety net hospitals like federally qualified health centers that tend to treat more underserved communities. The main issue with the “non-profit” status is that there’s an extremely high variance on the kinds of hospitals that benefit - we should narrow support to hospitals and places of care that need it.

Force non-profit hospitals to receive a meaningful amount of revenue from value-based care programs where they get reimbursed based on good patient outcomes e.g. two-sided financial risk agreements.

Stronger government-run care options and for-profit private systems instead of “non-profit” private health systems, but I feel like a lot of people calling are going to call me a communist for this one.

We have a rare opportunity to implement lots of “out there” changes now. Even the NFL was a “non-profit” between 1942 and 2015, it’s okay if we decide things are different today.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. Currently A One Man Non-Profit

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

The trends I have noticed, working in healthcare for over 30 yrs: the outsourcing hospitals do. No longer is laundry being done at the hospitals. Environmental services, patient transport, and food/nutrition are being contracted out to other companies where their employees get paid poorly. There is very high turnover in those areas. Clinical staff are now getting flexed out of their shifts early if the hospital census is low. The managers get rewarded for doing that flexing, with big bonuses. No longer can hourly employees rely on getting paid for a 40hr work week. Do you want someone taking care of you when they are worried about making their bills for the month? The bonuses that the administrators and CEOs make are disgusting. In my career, I’ve only worked at 1 hospital that dispersed a significant portion of “profits” to the employees without any hoops to jump through. If we get any share of “profits” now, we must meet unattainable metrics to where our yearly “bonus” is so small, the hospital must make numerous announcements prior so that we will even notice. (Usu less than $200 gross). The very institutions you rely on for care only care about MONEY; the people who actually care for you? (those who clean your room, nurse you, draw your blood, image you, feed you, move you, or otherwise touch you in any way- THEY (we) are the people who care about you.

As the judge mentioned, these non-profit hospitals are mostly a work of legal fiction. I believe that the right fixes here have to do with fixing the incentives. Of bureaucrats first and foremost.

I do not believe the solution is greater regulatory oversight. When jobs and employment are on the line, or a bad PR move on the line, it is unlikely that a regulator is likely to challenge the status quo. A bureaucrat is not empowered to make decisions that cuts deep into issue, and state/local elected officials would be more interested in jobs than getting into the weeds of complex medical care laws (I like to distinguish that the real issue is not a discussion of *health*care, but rather access to *medical*care).

If anything, your last point is probably the most salient: "Stronger government-run care options and for-profit private systems instead of “non-profit” private health systems, but I feel like a lot of people calling are going to call me a communist for this one." <-- this balances the needs of those with inadequate care with those who have the means of purchasing private medical care.