Race And Healthcare: Recognizing And Addressing the Issues Facing Black Patients

The systemic issues that plague black communities are extremely prevalent in healthcare, and we should think about how to address them

Like I’m sure many of you reading, this has been a really tough week. Watching the video of George Floyd was painful and heartbreaking. It didn’t feel like the right week to write another meme-driven healthcare newsletter - there are more important things going on in the world.

The death of George Floyd has sparked protests and discussion around the systemic issues around law enforcement and its mistreatment of the black community. I thought I’d use this week to talk about an issue I’ve been meaning to get to for a while - the systemic racial issues facing black patients today that are pervasive in healthcare today.

Specifically, I’ll talk about

Tuskegee, a historical atrocity that has created a foundation of justifiable mistrust between the healthcare community and black community

COVID and how diverse data capture is an underlying problem that needs to be addressed to make changes

What the disparity in services look like for black patients from a care accessibility standpoint and the issue that happen when actually receiving care

Upstream, non-healthcare factors that disproportionately affect black neighborhoods and lead to poor health outcomes

What we can do to fix some of these issues + open up the discussion for other ideas

Tuskegee

This conversation can’t be started without talking about our historical injustices, and none is more relevant than the Tuskegee experiment. It’s worth reading the original 1972 whistleblower article about it.

In 1932 a study of 600 black men in Tuskegee, Alabama intended to examine the development of syphilis in patients when there was no known cure. By 1947 penicillin had been discovered and was the recommended cure for syphilis. However, the researchers behind the study convinced local physician running the study to allow the participants syphilis to go untreated despite a known cure.

By the time the whistleblower article was published, 28 participants had perished from syphilis, 100 more had passed away from related complications, 40 spouses were diagnosed and it passed onto 19 children. This tragedy led to the publishing of the Belmont Report and the establishment of the Office for Human Research Protections, which created a lot of the bioethics principles behind the design of modern trials.

This is a tragedy we shouldn’t forget and underpins a lot of the mistrust that the black community feels towards the healthcare system in America.

COVID and Data Capture

It’s impossible not to connect George Floyd’s struggle to breathe and COVID’s disproportionate suffocation of black communities. The COVID Tracking Project actually tracks COVID’s impact by race, and even with the data available black communities are represented 2x more in reported COVID deaths vs. their representation in the US as a whole. You can see how bad it gets on a state-by-state level in the data when you look at States like Wisconsin, Maine, New Hampshire, etc.

But what this data also shows us is just how bad our data capture about race is and how we seem to de-prioritize it as a factor in healthcare. The fact that 48% of reported cases don’t have a race tied to them and states like Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Georgia are missing 50%-70%+ illustrates that fact. We can’t improve what we don’t measure properly.

It’s worth noting that this is a widespread issue even sans COVID. This study talks about how much of race or ethnicity data is straight up missing, and even the data that’s there is off.

Among the 160 million patients from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project and Optum Labs datasets, race or ethnicity was unknown for 25%. Among the 2.4 million patients in the single New York City healthcare system’s EHR, race or ethnicity was unknown for 57%. However, when patients directly recorded their race and ethnicity, 86% provided clinically meaningful information, and 66% of patients reported information that was discrepant with the EHR.

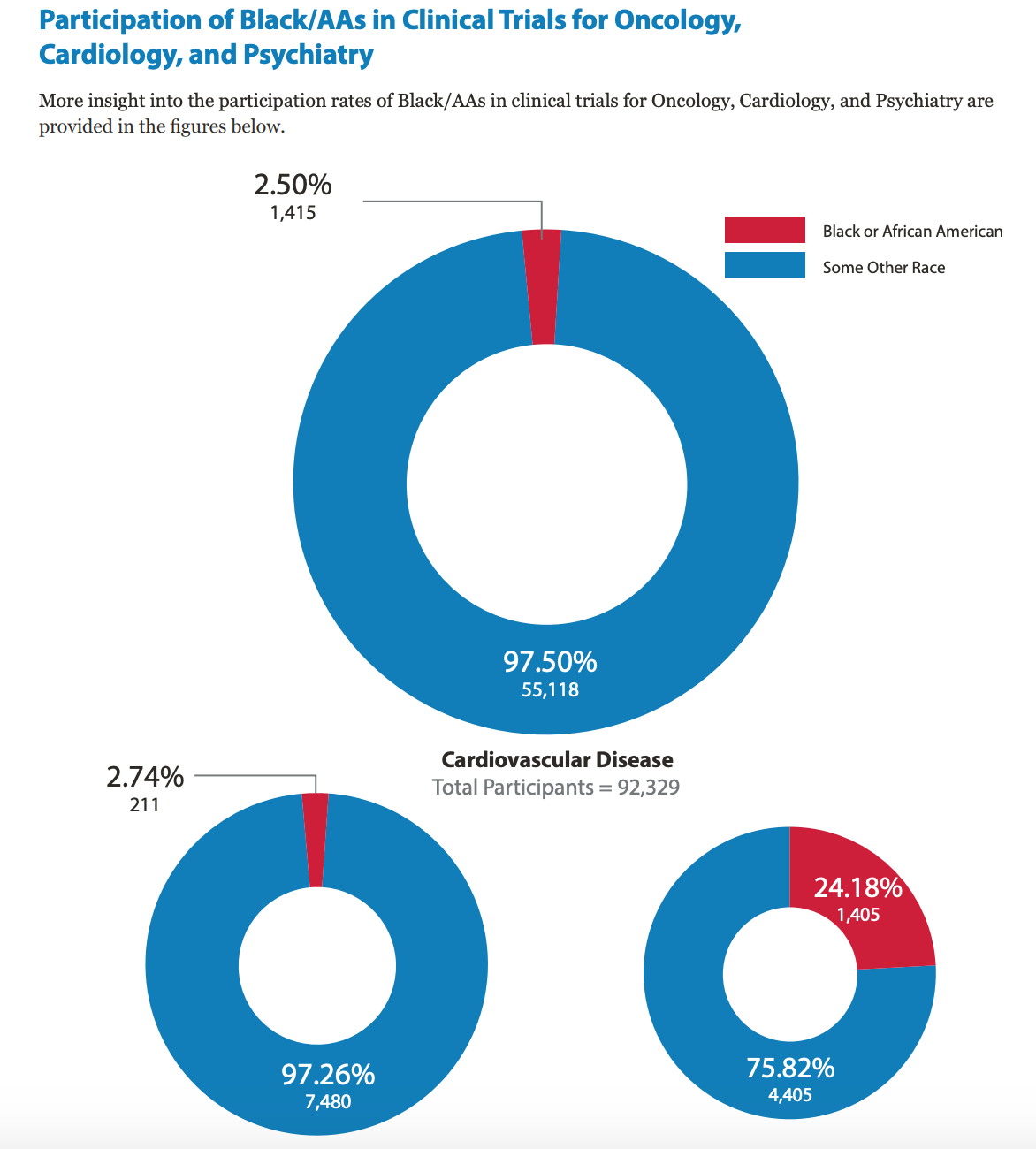

Another facet of this same issue is that lack of participation in research and clinical trials. While total trial participation of black patients in trials is close to proportional representation in the US population (~13-14%), the types of trial matter. Black patients are way underrepresented in areas where cutting edge medicine is being developed (oncology) and in disease areas that disproportionately affect black people (cardiovascular disease).

This is especially critical as increasingly more personalized immunotherapies come on the market, since the immune response actually has quite a wide variance between races. You can read more about the differences in how various cancers and their immune response vary between races and ethnicities here.

This lack of healthcare data about the impact of care on black patients is going to exacerbate many of the health inequities we already see. Not only are new therapies going to be developed without their representation, but as we move into areas where clinical decision support tools and AI are guiding physicians to make decisions, we’re already seeing how a lack of good training data is having unintended consequences.

For example, this paper found that an algorithm designed to assess patient’s risk (and therefore deploy more care to those patients) suffered from bias because it used future cost to make the determination. However, for many reasons ranging from distrust of the medical system to lack of accessibility and ability to pay for care, black patients tend to get less care (about $1800 less) and would therefore be less likely to be flagged as at-risk.

In this case the bias was caught and fixed. But as the algorithms become more complicated and we rely on them more, the data and models we use influences how care is delivered and how medicines work. It’s not truly “precision medicine” if data only works for a few groups.

Disparity in Services

Very recently ProPublica wrote this extremely well-written piece about the amputation epidemic that happens to black patients in the South. There are so many paragraphs I would want to quote, but this one is haunting.

Marie Gerhard-Herman, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, chaired the committee on guidelines for the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. She told me that angiography before amputation “was a view that some of us thought was so obvious that it didn’t need to be stated.” She added: “But then I saw that there were pockets of the country where no one was getting angiograms, and it seemed to be along racial and socioeconomic lines. It made me sick to my stomach.”

Stokes wasn’t at immediate risk of losing her left leg when she met Fakorede, but pain prevented her from walking. She had a severe form of the disease, and Fakorede booked her for an angiogram and revascularization. He inserted a wire into her arteries and cleaned out the clogged vessels, letting oxygen-rich blood rush to her remaining foot. While she was recovering in Fakorede’s lab, she thought about her neighbors who had the same problems. “I really don’t like what’s happening to us,” she said to me. “They’re not doing the tests on us to see if they can save us. They’re just cutting us off.”

People were getting limbs chopped off because proper screening wasn’t done at anyone point in the process, from primary care for early detection to pre-surgery to understand whether surgery was necessary.

The structural issues here are two-fold. One is the lack of accessibility to proper care and the second is the implicit bias that happens when black patients get care.

If you look at the data side-by-side of where predominantly black counties in the US are vs. where the primary care shortages are, you can see that almost every area in the South is either below or significantly below the national average. In the ProPublica story they talk about primary care physicians seeing 70+ patients per day and neither have the time nor reimbursement incentives to run a lot of the necessary screening tests. Lack of access to specialists, especially in some of the rural parts, only compounds these issues.

Now on top of that, you can see how the ability to pay factors in. Many of the predominantly black states do not have Medicaid Expansion. This cause many black adults to fall into a coverage gap, where they make too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for premium subsidies in the individual health exchanges. If you can’t pay for care, you avoid care.

Even once you do finally get care, treatment looks different between races. There are lots of studies that look at some of the more implicit biases where this happens, but two well-studied and more explicit ways this manifests is in pregnancy and pain management.

The US is one of the worst scoring countries when it comes to maternal mortality. This is particularly bad because most of the underlying causes for maternal mortality are well-studied and preventable. Even sadder is how this disproportionately affects black women in the US. There are several theories as to why this is, ranging from implicit bias of providers who dismiss the concerns of black patients, to a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease the leads to them. It’s worth noting that the reason we have this data is because a checkbox was added to death certificates once it was known that this issue was not being properly captured or study (which goes back to my earlier data point).

Pain is another area we see this disparity. Black patients are under treated for pain symptoms, and there are still widespread myths that the black patients feel less pain because they have less nerve endings or have stronger bodies in some capacity. 40% of first- and second-year medical students endorsed the belief that “black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s.”

Compounding these perception issues are the fact that we simply don’t have enough black doctors vs. their population representation, despite research showing that black patients are much more likely to listen and trust recommendations from other black doctors. It’s not rocket science that you’ll listen to someone that better empathizes with your issues and you’ll probably receive better care.

The Upstream Factors

The issues that lead to these poor outcomes start outside of the hospital. The AHRQ puts out a National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Report which benchmarks a large series of healthcare quality markers for each race. I took the data from the 2018 report and after re-discovering how awful converting data from a PDF to Excel is, I filtered by the quality metrics where black patients were most significantly worse than white ones.

There are a few standouts where the measures are significantly worse in black populations vs white ones: HIV, Asthma, hypertension, and diabetes-related complications.

Each of these are public health issues. Diabetes and heart disease are byproducts of disparities of food deserts in black zip codes. Childhood asthma is pretty clearly tied to zip code and a byproduct of indoor and outdoor environmental factors in neighborhoods. New HIV diagnoses in black patients coincides with low rate of PReP adoption in black patients + lack of awareness of HIV status.

If we want to understand why black patients end up in the hospital, we have to realize that a lot of these issues are happening in the home itself. Programs to make it easier to buy fresher produce have shown promise and outcomes at small scale. Better monitoring air quality and increasing awareness of issues like secondhand smoke and mold can help address asthma. I’m a big fan of the PReP campaigns, but there’s still a lot of work to be done in the hotbeds of new HIV cases.

How Do We Go Forward?

We’ve made major headway in addressing some of the major health issues that have disproportionately hit black patients. But we still have more work to do.

Recognizing and studying the biases

We need to recognize where and how these biases manifest. These are just a few, but more studies done to understand these systemic issues is important. To me this kind of racial inequity in healthcare is really pernicious because there are rarely extreme catalyzing events like George Floyd’s for people to react to and demand change. This kind of inequity grows slowly and kills more silently.

Business model incentives and public-private partnerships

We need to create sustainable business models so that companies are financially motivated to seek out these inequities and rectify them. We’ve seen some examples of this with Medicare Advantage plans, where private companies have an incentive to seek out and care for their sickest patients including addressing the non-healthcare factors in their lives. Managed Medicaid companies like Cityblock are doing something similar for the lower-income Medicaid population.

I’d love to see more innovation and incentives here, especially from the provider/physician side, to better address underrepresented demographics like black patients. If there are actual business models to address this, it’ll be more sustainable change instead of lip service. Everyone in healthcare knows that addressing these “social determinants of health” lead to better outcomes, but I’d like to see more state-based incentives here.

We need at-scale initiative experimentation here to figure out what works. I’m watching North Carolina’s Section 1115 Medicaid Waiver which allows them to spend federal Medicaid dollars on the non-medical care. UnitedHealth’s investment in housing for its more at-risk Medicaid patients through state and federal tax-credit programs is another program worth watching and seeing what works. I’d like to see more of these kind of public-private dollars at work to focus specifically on black communities and the unique set of problems they face.

Working within the black community to deliver care

There’s more work to be done to bring care to the black community in a way that works closer with trusted community leaders and in more accessible settings. A study I quote all the time brought specialty pharmacists to screen predominantly black clients into black-owned barbershops to be screened for hypertension and have medications prescribed. The control group were the barbers only encouraging patrons to go to the hospital for screening and care.

I love this study not only because it demonstrated bring care INTO the community actually works, but also because of how many people actually stayed in the trial once enrolled. It’s possible to design trials and research with black communities in mind, and we should think about more designs like these. And we should think about designing research and studies to focus specifically on black patients instead of simply including them in general studies. Get involvement from the black community to deliver results and better healthcare strategies directly back to the community.

The study also demonstrates how we can better work with non-physicians to help increase the reach of care in areas where care might be more inaccessible. I think tech can play a meaningful role here by equipping physicians and non-physicians alike with the tools to do more screening + access to telemedicine expertise where access to specialists might be difficult and primary care physicians are already strained.

Proper labor and care triaging can increase touch points with at-risk patients and make sure problems are caught early and handled by a physician, nurse, social worker, etc. depending on the severity. A lot of those diabetes-related amputations from the ProPublica story could have been addressed earlier if the at-risk patients were caught earlier.

More data for better measurements

We need to get better data to understand the impact of these disparities on black communities and create better drugs, care guidelines, decision support tools, etc. We can’t fix what we don’t measure, and the absence of usable data here is going to widen these disparities.

For example, this study demonstrated that albuterol actually has a lower effectiveness in black patients with asthma due to genetics. This is extremely troubling since albuterol is the most commonly prescribed medication for asthma and and extremely high cause of death amongst black children.

We need to use better data to create new systems of delivering care.

Public health campaigns

We need more aggressive public health campaigns to address some of the specific issues that disproportionately affect black communities like HIV, Asthma, heart disease, and diabetes. Some potential examples:

More well-funded PReP and contraceptive programs that can distribute supplies independent of insurance status.

Distribution of air quality monitoring tools to address the environmental issues that underly respiratory diseases.

More funding to SNAP and EBT programs with incentives to buy fresh produce or meals and education programs around benefits of healthy cooking/food preparation, especially tailored to people at risk for different chronic diseases.

Conclusion

I’m not sure what needs to happen for us to realize that these are disparities that are very real and need to be addressed. What will be our George Floyd catalyzing event for us to talk about restructuring the healthcare system? If any of you have ideas on what we can be doing to push this conversation forward, I’m all ears and eager to do my part.

We need to have some serious reflection in this country around how the systems we have in place do a disservice to black people of the US.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil

Twitter: @nikillinit